Bridged Amplifier Headphones Adaptor

A question I've been asked multiple times is how to connect headphones to a stereo bridged amplifier.

With a non-bridged amplifier, the advice can be followed for ESP Project 100 - Headphone Adaptor for Power Amplifiers. Before you start here, read the linked article first.

With a bridged amplifier, per Rod's advice, the short answer is you can't normally. A bridged amplifier has the negative speaker output is connected to a second inverted amplifier instead of the common power ground and is independent for each channel. With headphones, the audio return is ground and is shared in a normal 3.5mm socket.

Therefore, unless you're willing to replace the whole cable to your headphones with 4-core cable and a 4-pin DIN or similar adaptor, you cannot connect a bridged amplifier. I suggest not to modify headphones in this way and make them incompatible for any other system without a further adaptor and make them unsellable in future if you want to upgrade.

However, a bridged amplifier can normally be treated as two independent amplifiers. One is non-inverting (typically the positive speaker terminal) and the other is inverting, but both signals can be referenced to the power or audio ground.

One single ended output of a bridged amplifier is usually plenty of power for headphones, so, what if we just forget the negative speaker output and connect our headphones adaptor between the positive only speaker output and the common power / audio ground?

With dual rail power supply amplifiers, this is possible since the positive speaker output will have only a small DC offset and the AC audio will swing positive and negative relative to the common ground. This voltage can be attenuated through the resistors in the headphone adaptor to make it work with headphones instead of speakers.

The second half of the bridged amplifier driving the negative speaker terminal would be left unconnected. They'll be some power wasted in the quiescent current of the amplifier, but since it is unloaded, it will not waste significant power.

But we have now may have a second problem. Many bridged amplifiers are typically single supply amplifiers. These apply a DC offset of around half the power supply voltage as a virtual ground. For example, you'll see around 6V DC measured between 0V ground and the speaker terminal for an amplifier powered from 12V DC. Since both the positive and negative speaker outputs have the same DC offset, this is not a problem for the normally connected speakers since no DC current will flow through the speaker when both terminals are at the same potential.

If we connect our headphone adaptor between the positive speaker output and the 0V common ground, that DC offset will flow from the positive speaker terminal to ground and the headphones will likely burn out.

Enter the capacitor. This is used on single-ended single-supply amplifiers to protect speakers from this DC offset and can also be used to protect headphones. The capacitor gets charged to that half DC offset voltage during power on, but then blocks the DC. As the amplifier raises or lower its output voltage, the capacitor would charge and discharged through the speaker or headphones, effectively replicating the audio AC wave.

The capacitor has to be sized large enough to pass AC down to 20Hz (our hearing limit). As headphones plus the adaptor represent a higher impedance than the typical 8 and 4 ohm speaker loads, the capacitor can be smaller whilst still providing a low frequency cut off lower than 20Hz.

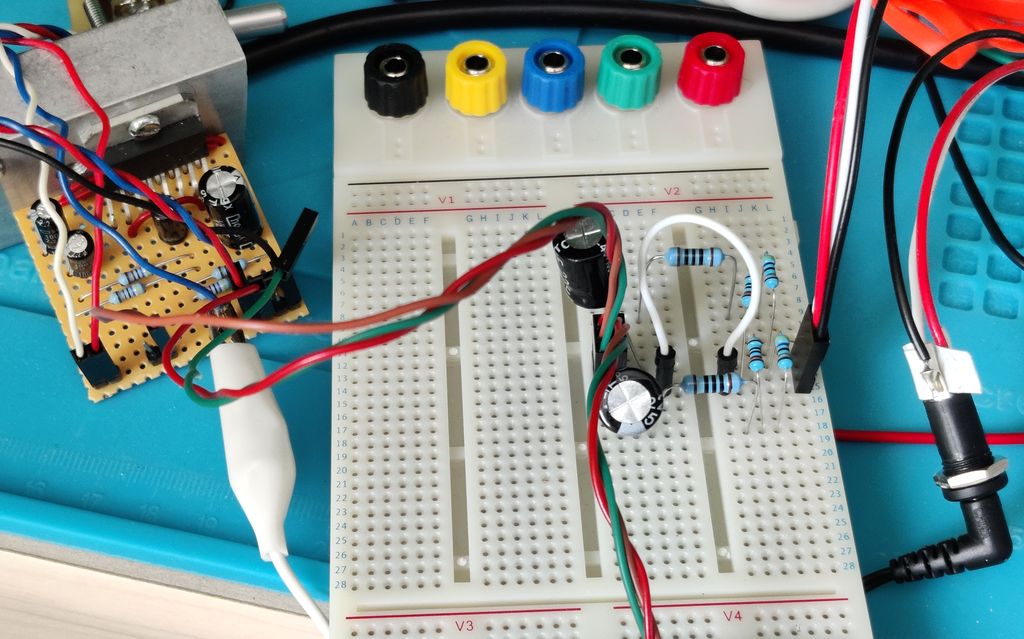

There will be a pop on power on, off and disconnecting / connecting headphones. I tested it out with the above component values on a TDA7266 amplifier and some old in-ear earphones and there is a pop, which is worse for power on than off / disconnecting. It was not too bad though (more of a click) and certainly didn't blow out my earphones or eardrums.

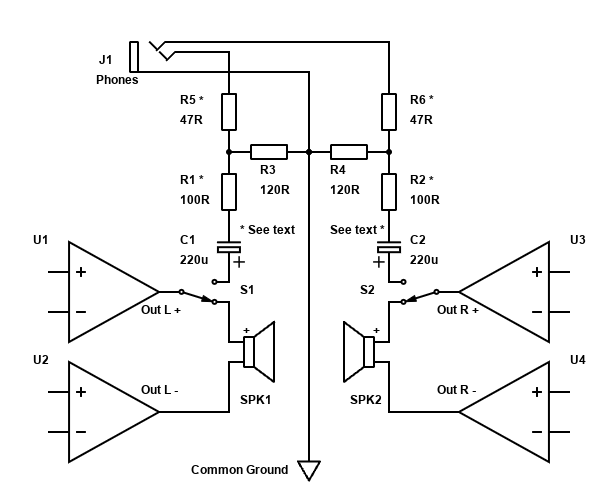

Above is the schematic of the adaptor. The resistor values (resistance and power) for R1 / R2 and R5 / R6 should be followed per ESP Project 100 article but your power amplifier output will be roughly a quarter of the bridged output.

For example, if your amplifier is a TDA7297 / TDA7266 with 8W output into 8 ohms speakers at 12V, then single ended it will only give a little over 2W output into the same 8 ohm load.

Rod Elliott doesn't have component values for an amplifier smaller than 10W, but I found the suggested component values for this configuration gave around the same level of volume with the amplifier at max volume compared to connecting the headphones directly to my Smartphone (via the USB-C DAC adaptor). On the oscilloscope, I measured 90mV RMS at the Smartphone output with a 1kHz tone generator and measured 94mV at the output.

If you want a higher output, feel free to lower the resistors. Output impedance may be lowered as you do this, so I suggest you breadboard the adaptor first and listen to check performance.

Please Note - Capacitors C1 and C2: If your bridged amplifier is not driven from a single supply and there is no DC offset at the speaker terminal, then do not use the capacitors as they will fail once reversed biased to ground. Use a multimeter on the DC setting between the speaker terminal and ground (not the negative speaker terminal) to see if there is an offset.

For C1 and C2, I've suggested 220µF, but 100µF would also work and both would provide a frequency response cutoff somewhat below 20Hz. The positive lead of the capacitor needs to be at the amplifier output, so the capacitors is biased correctly. The capacitor voltage rating must be higher than the supply voltage. For an amplifier running off +12V, that would be 16V capacitors.

Capacitors of this size would be electrolytic. Some people may be bothered that is impairs sound quality and you may be able to improve high frequency clarity by connecting a polyester capacitor (470nF to 1µF) in parallel with the electrolytic, but there probably be no audible difference.

To switch between speakers / headphones, a dedicated DPDT (Double Pole Double Throw) switch must be used (this is shown as S1/S2). For powerful amplifiers, this must be a heavy duty toggle or rocker switch. The common terminal connects to the amplifier +ve output and this allows you to switch between the speaker and headphone adaptor. When the speaker is connected, the headphone adaptor does nothing. When switched to headphones, the speaker is disconnected from the amplifier +ve output and the -ve output essentially becomes unloaded with the +ve output now redirected via the headphone adaptor.

Conclusion

Do I recommend this? Not really. If you're building our using a bridged amplifier just for headphones, then there is no sense to that.

For small projects / amplifiers that you want to add a headphones connection to, and you don't have expensive headphones and expect Hi-Fi quality sound, it should work fine. For high fidelity 'phones, invest in a building a dedicated proper headphone amplifier (such as ESP Project 113 - Headphone Amplifier) for a better solution. This or a similar amp can be connected to the output of your preamp section in a DIY project.

Remember that you must never connect both negative and positive speaker terminals to the adaptor. The headphones return must go to the audio / power ground. For an existing amplifier, the outer sleeve of a phono socket could work for this, but this may result in noise as you're sending more current through the preamp than intended.

The other problems to be aware of is the power on/off and connection pop / click that may bother you, but as a practice you should always switch on an amplifier, turn down the volume and then put on your headphones whilst gradually increasing volume to a comfortable level. Attenuating an amplifier intended for speakers is also wasteful and you'll also need a big dedicated switch to toggle between headphones and speakers since you cannot use the integrated switches in common 3.5mm adaptors.

Finally, be aware of the power potentially available. Even though we're using half of the amplifier, the power output is still considerable and turning up the volume may damage your headphones, and your ears. Permanent hearing damage from high SPL (Sound Pressure Level) is possible with many headphones and earphones with just a few mW of power. Max volume can be restricted by increasing the values of the resistors, but then you have to turn the amplifier volume higher to reach normal levels and that might result in a surprise high volume once you switch to speakers again!

However, a component of DIY is learning and experimenting. So, if you've built a bridged amplifier perhaps from one of my articles and want to add a simple headphones output without building a dedicated amplifier - this makes it possible. Just take care!

References that helped and further reading: